Reviews

Madonna

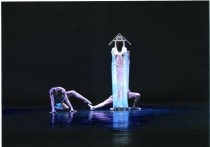

Rebecca Valls' Madonna, is a choreographic gem. The title and sculpture/set piece I see as the stage lights rise welcome me to a world of spirituality. The haunting score by Zoë Keating reinforces the sense that I have left the temporal realm. A "child" reflecting/worshiping at the sacred spot of her deceased mother's wedding dress is absorbed in memories which soon become abstractly re-enacted as the "parent" leaves her sanctuary and becomes embodied. In an evolution of non-literal, delicate encounters, I am swept up in thoughts and feelings about departed saintly women in my own experience. The movement language emphasizes linearity, directness and gentleness. It's mostly abstract nature allows me to enter the piece on my own terms. There are many fascinating interactions, some with highly detailed gestural components, often followed by sweeping phrases in time and space. The highlight for me comes near the end, when both dancers are sitting down stage right, and the mother (for a moment only) seems to weep as she embraces her child. At the end, as the Madonna returns to her sanctuary, the worshiper is left alone, wanting to leave but somehow unable to let go of the dress and all the memories and feelings it symbolizes.

I saw the piece performed many times over the course of a week by SUNY Brockport dance professor Suzanne Oliver and one of her students, Sarah Morrill. I admired the unforced clarity of their dancing. A couple of weeks later, I witnessed a performance by two students, whose movement signatures are quite different from those of Oliver and Morrill. These two young artists brought out different potential aspects of the choreography. Because they invested more heavy and strong weight in the piece, it seemed somewhat more worldly. I enjoyed both interpretations.

Memoirs of the Sistahood - Chapter Two: House

Members of a large Catholic family who experienced childhood in

southern Louisiana during the 1950s, sisters Becky Beaullieu Valls and Babette Beaullieu build upon a rich soil

of memory for their dance theatre collaborations, Memoirs of the Sistahood. Nearly

two years after the debut of Chapter One, the duo has delivered their second

installment, Chapter Two: House. A video recap opens the show. Even to the

uninitiated, however, the visual prologue is nonessential. This production is sufficiently distinct. Like a house, it is intelligently designed with pattern, substance, and mortar structured around a

supportive framework.

Of course, every house needs a hostess. In a vintage cinch-waist dress, narrator Kathy Hallmark delivers an introduction with the saccharine, matter-of-fact tone of a 1950's television housewife.

"All houses are dwellings," she quotes Paul Oliver's reference book on vernacular homes throughout the world, "but not all dwellings are houses. To dwell is to make one's abode: to live in, or at or

on, or about a place." Like Oliver's book, Chapter Two: House, examines different

types and ways to dwell.

Valls glides between choreographic modes as easily as one might move from room to room. She begins with a minimalist, pure movement approach, then displays skillful confidence as the work

shifts to burlesque. In Act I, which examines dwellings as structure, Valls shows restraint, choosing not to hide or overdress the circles, lines, and spatial devices that form the skeleton of her

choreography. Later, Busby Berkley inspired formations give way to a lively mambo, danced by sepia-toned housewives armed with cornflake boxes and kitchen gadgetry.

Veteran performers, including Valls herself, anchor the company. Dancers, Toni Leago Valle, Jenny Dodson (formerly Magill), and Joani Trevino are consistent in their actualization of Valls' smooth,

expansive movement style, and they transition easily to comedic and presentational delivery.

Clearly, the collaborators are all on the same page with House. Deborah Schlidt's

dreamy film collage weaves in and out of the action as naturally as any performer making an entrance. Images of various types of dwellings, from hovels to tract houses, segue to demolished and

water-logged homes. Reclaimed by nature with the brute force of Hurricane Katrina, these homes (or ones like them) may have given up parts of themselves for repurposing in Babette Beaullieu's found

object sculpture and set pieces. Dancers first appear in costumes the color of clay and mud. Attentively designed by Cherie Acosta, these basics are detailed with netting and natural fabrics that

echo the weathered patina of the doors, windows, and boxes Beaullieu has fashioned to represent the family homestead. Among these pieces, a playful dinner scene and a bed of sleeping children are

given a hazy luminescence by lighting designer Kris Phelps that recalls precious home movie footage of the Beaullieu family.

It all works together, even as these collaborators rather craftily bring their 1950s backdrop to the forefront. I Love Lucy clips play dreamily as the childhood game of playing house transitions effortlessly to a satiric

portrayal of real life domesticity. Text from Housekeeping Monthly's "The Good

Wife's Guide" illustrates the expectations and constraints placed on women saddled with running a home. Fifties era musical selections such as the Dean Martin

classic, Sway, fuel the wry comedy which culminates in a kitschy "mobile home"

show. The dancers flaunt their best runway sashay in a segment that in lesser hands could have capsized the production.

The milieu of 1950's iconography remains upright however because Valls and Beaullieu, with their collaborators, thoughtfully maintain a through line. It is no small feat to coalesce this array of

concepts. Chapter Two: House reaches coherence because the team has built a solid

framework and follows-through with strong images and clear ideas. The enchanting and harmonious collaboration brought the audience to their feet on opening night.

Nichelle http://nichelledances.wordpress.com

Memoirs of the Sistahood: Chapter One

Works of highly private inspiration have a long and distinguished history of being poor public entertainment. That fact alone makes this dance-filled “memory play” by choreographer Becky Valls and her sculptor sister Babette Beaullieu Wattigny and achievement more than a little notable. As presented at DiverseWorks, Memoirs, was “private” in the way that a short novel might be, or perhaps a small experimental film free of major stars. But it seemed a departure from most dance evenings – even from admittedly boundary-free “modern dance”. Memoirs was cinematic more than anything else, an act of visual storytelling that used dance along with projected film, exquisite music and intriguing sculpture. In short, it worked.

We’re not sure exactly why “sisterhood” was expressed in the title as “Sistahood,” since that seemed “ghetto” in a way that neither the creators nor their creation were or wanted to be. The story involved the interwoven lives of six French Catholic sisters coming of age during the 1950s in French Catholic south Louisiana. Anytime there was a specific reference in Memoirs, that was the place and the time. Yet nearly all the individual, almost unrelated dance segments were either too ambiguous to be about anything, or too universal to be limited to any single thing. The core experience was growing up, specifically as a girl with lots of sisters – through life with lots of siblings was common enough among Louisiana’s French Catholics. The evening floated by as a series of half-remembered, possibly half-dreamed vignettes, news clippings from a youth presumably remembered from the distance of age. That last conviction seemed to grow from the way Valls looked at even the most light-hearted of family times with longing, as though reaching out to them across the decades without ever truly reaching them. Nostalgia? Perhaps. But not the cheap, store-bought kind. This was passion for an essential past, coming from a very deep, sometimes dark and ultimately loving place.

The visible center of Memoirs was the graceful, loping, curling and circling choreography of Valls, who also serves as director of the dance program at Rice. There were clear debts here to that other chronicler of ever-symbolized young womanhood, Agnes DeMille in such pieces as her ballet for the musical Oklahoma. The dancers always managed to entertain while emotionally affecting us, and never more than in those segments featuring Valls herself. Her facial expressions and movements were the “voice” of the narrator, even though she and her sisters also provided spoken words to set up many of the scenes.

All pieces were delivered with enthusiasm, capable of acting and absolute belief by Kara Ary, Mechelle Flemming, Jenny Magill, Stephanie Rodriguez, Joani Trevino, and Toni Leago Valle, with an entertaining assist from Corian Ellisor, the lone male allowed into this sleepover. Sets and props were mostly pieces created from old wooden doors, windows and other found objects by Wattigny. And the evening’s most touching backdrop was an incredibly edited montage of family home movies, tossed up on a screen in all the scratchy wonderment of people, places, and things never to be seen again. Except that, thanks to this particular and talented sisterhood, they can be. And they were.

http://issuu.com/artshouston/docs/2008_01_issuu

Memoirs of the Sistahood: Chapter One

I thought childhood was pretty much about learning to tie my shoes, getting along with a slew of people who all have the same nose, and generally speaking, growing up. After seeing Memoirs of the Sistahood - Chapter One, a new work by sisters and collaborators Becky Beaullieu Valls and Babette Beaullieu Wattigny, I see childhood in a whole new light-it's about gathering material, for what else, a smashing show. All that time the Beaullieu sisters, Beth, Becky, Babatte, Bonnie, Bitsy, and Barbara, where trying to make it to church on time, they were really rehearsing. And what a rich soup of material sisters Valls and Wattigny have to play with, growing up in a Catholic family in Louisiana during the 1950s.

The Beaullieu sisters create a dreamscape with Wattigny's sculptural pieces that transform into portals for Valls' dances. Using decorative back porch doors, intricate narrow closets that resemble medieval alter pieces, and rustic window frames, Wattigny colors and covers the stage with entrances, exits, and hiding places. They serve to let the performers weave in and through their own whimsical logical time line and completely free us from any linear narrative. Glorious stage pictures elegantly frame Valls' dances.

Valls crafts her choreography from a fluid post modern dance style, while also playing off recognizable gesture and everyday actions. As each sister enters from one of Wattigny's colorful back porch doors in a slow motion dirge, they carry a sculpture crafted from nature on their backs, as if to resurrect something from each of their pasts into the present. One carries a collection of sticks, another a vessel, symbolic of traveling through time, each with a distinct gift. One ensemble section completely conjured the tight living quarters six sisters must have survived. Valls herself danced a sweet duet with Mechelle Fleming. One wonders if Valls here is a time traveler and is dancing with herself.

All collaborators contribute to Memoirs' sense of wholeness. The sound score combines eerie tunes from Dead Can Dance and the like with Misha Penton's ethereal instrumental pieces. Kris Phelps' lightening emphasizes private spaces and a suitably dreamy atmosphere. A video montage by Deborah Schildt also hopscotches through time, landing on memorable moments, birthdays, holidays, vacations, giving us a glimpse of family record without a litany of actual events. Costumes by Valls and Wattigny draw from Louisiana folklore, 1950s fashions, and southern debutante glamour. On a post-show close inspection, one costume reveals a trim of doll parts, and other junk drawer delights. Both costumes and sets hold their own as an installation piece as well as a performance. In fact the piece concludes by the performers bringing all the visual elements together for one last look, a final tableau.

The capable performers included Kara Ary, Mechelle Flemming, Jennifer Magill, Stephanie Rodriguez, Joani Trevino, Toni Leago Valle, and Corian Ellisor (as the solo male child). Valls and Wattigny made smartly positioned cameo appearances as well.

A few bumps down memory road included: an occasionally overly cluttered stage, abrupt and long blackouts, and some sheer practical concerns about moving such intricate and complex objects on and off stage.

There are many lovely elements to this work, but chief among them is the pair's commitment to telling a new story rather than falling into the dreaded page-from-our-journal- autobiographical-syndrome. There's little attempt to use personal history as just that, the truth. Memoirs of a Sisterhood - Chapter One derives much of its drive from mining the power of memory alone, most specifically the embellishment of imperfect recollection. Memory is a dance, an art in and of itself. Memory can only be a creative act. When we remember we re-create; Memoirs enlists this process exactly.

A scene with all seven children waving from a speeding boat proved my point about the meaning of childhood. They are waving at us from the past, as if in that actual moment, they all knew that it was a keeper.

I doubt I was the only audience member who wanted to wave back in thanks for the Beaullieu family coming into my life.

Memoirs of a Sisterhood- Chapter One continues on December 14 & 15th at DiverseWorks. Call 713-822-0144 or visit www.diverseworks.org.

Static

Angels in Houston: A Weekend of Contemporary Dance

“The bill included a nod to veteran Houston choreographers Victoria Loftin, Jennifer Wood, Becky Valls, and Priscilla Nathan- Murphy, and celebrated newcomers to the festival Kathy Dunn Hamrick, Suzanne Oliver, and Stanton Welch. For the first time, students took part, and judging from their sound performances, I imagine they will be back next year. Also of note, Valls, Loftin, and Oliver hark from area college programs (Rice University, University of Houston, and San Jacinto College) where too often their work is off the usual dance radar.

Valls' Static, wonderfully danced by a mix of University of Houston students and faculty, oozed post-modern angst in a well-crafted dance. Set to Dead can Dance tunes, Valls captured an essence of our overly wired modern ways”.

Facade

Dancers lend emotion to enigmatic works

Darkness prevails at the Big Range Dance Festival's Program D, in the lighting and in the quirky attitudes of works by Rebecca Valls, Erin Reck, Leslie Scates and Jane Weiner.

Erica Lewis, Jennifer Magill and Toni Leago Valle gave all their acting energy to Valls' Façade. (Thomas Henderson didn't.) But the humorous dance's three sections were as enigmatic as the score, which involved nonsensical, abstract poetry by Edith Sitwell and Iva Bittova. (The first dance turned too childish when Lewis and Henderson had a sword fight with drinking straws.)

On the Wing

'Weekend of Texas Contemporary Dance' stretches minds

"The line between dance and performance art seems to be blurring - that's the vibe I got from the 10th annual Weekend of Texas Contemporary Dance. This is not a bad thing; it's a sign that local artists are mulling ideas - and, in the process, moving audiences to think.

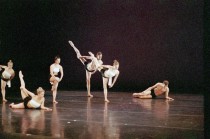

This year's showcase was entertaining and well-balanced. On the pure dance side, Rebecca Valls' charming On the Wing conjured up a flock of migrating birds. Terrain and seasons "changed" with the ethnic overtones of Bruno Coulais' music, gestural embellishments in the choreography and "plumage" that came and went from the black-and-white costumes. Dancers Jessica Harper, Christian Holmes, Jenny Magill, G. Joseph Modlin, Kristina Perello and Lindsey Thompson gave the birds quirky character and showed good technique in the many long, one-legged balances".

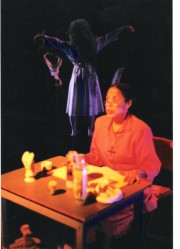

Palmetto…The Healing Beliefs of Louisiana Voodoo, Catholicism and Cajun Treaters

“Palmetto…the Healing Beliefs of Louisiana Voodoo, Catholicism and Cajun Treaters offered the night’s only levity. Conceived by choreographer, Becky Valls, and Louisiana musician-storyteller, Austin Sonnier. Jr., it portrayed- with rich humor- the blurry lines between religion and witchcraft in the Cajun/Creole culture.

Dark lighting enhanced the mysterious mood as a highly animated Jean Donnato read story poems about characters who practiced Voodoo. Valls enacted some of the stories through dance, wearing a long wig of moss for one. During the funniest sections, the two women feigned piety, reciting the Rosary like vacant robots, then sped through the final prayers so they could relate some superstitious do’s and don’t’s of Cajun healing rituals”.

Static by Becky Valls

Angels in Houston: A Weekend of Contemporary Dance

“The bill included a nod to veteran Houston choreographers Victoria Loftin, Jennifer Wood, Becky Valls, and Priscilla Nathan- Murphy, and celebrated newcomers to the festival Kathy Dunn Hamrick, Suzanne Oliver, and Stanton Welch.

Valls' Static, wonderfully danced by a mix of University of Houston students and faculty, oozed post-modern angst in a well-crafted dance. Set to Dead can Dance tunes, Valls captured an essence of our overly wired modern ways”.

Facade

On the Wing

'Weekend of Texas Contemporary Dance' stretches minds

“The line between dance and performance art seems to be blurring — that's the vibe I got from the 10th annual Weekend of Texas Contemporary Dance. This is not a bad thing; it's a sign that local artists are mulling ideas — and, in the process, moving audiences to think.

This year's showcase was entertaining and well-balanced. On the pure dance side, Rebecca Valls' charming On the Wing conjured up a flock of migrating birds. Terrain and seasons "changed" with the ethnic overtones of Bruno Coulais' music, gestural embellishments in the choreography and "plumage" that came and went from the black-and-white costumes. Dancers Jessica Harper, Christian Holmes, Jenny Magill, G. Joseph Modlin, Kristina Perello and Lindsey Thompson gave the birds quirky character and showed good technique in the many long, one-legged balances”.

Palmetto…The Healing Beliefs of Louisiana Voodoo, Catholicism and Cajun Treaters

Diverse Works' 12 Minutes Max

"Palmetto...the Healing Beliefs of Louisiana Voodoo, Catholicism and Cajun Treaters offered the night's only levity. Conceived by choreographer, Becky Valls, and Louisiana musician-storyteller, Austin Sonnier. Jr., it portrayed- with rich humor- the blurry lines between religion and witchcraft in the Cajun/Creole culture.

Dark lighting enhanced the mysterious mood as a highly animated Jean Donnato read story poems about characters who practiced Voodoo. Valls enacted some of the stories through dance, wearing a long wig of moss for one. During the funniest sections, the two women feigned piety, reciting the Rosary like vacant robots, then sped through the final prayers so they could relate some superstitious do's and don't's of Cajun healing rituals".

News

Becky received tenure at University of Houston and is now an Associate Professor.