Memoirs of the Sistahood Reviews

Memoirs of the Sistahood - Chapter Three: Ave Maria

Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans March 3, 2012

Peer Review:

Jeffrey Gunshol, Professor of Practice

Tulane University

Department of Theatre and Dance

I am writing to reflect, as a colleague, upon a choreographic work created by your professor Becky Beaullieu Valls but before I get into the specifics of Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria I would like to mention a few overarching things I ascertained after seeing the company perform.

Becky Beaullieu Valls has an intricate understanding of the body, her movement, and dance technique as a means to an end. The dancers showed an impressive command of their instruments and an ability to execute technical movement. Not only did the dancers show an advanced level of contemporary modern dance technique but displayed a nuanced and sophisticated understanding of how the technical movement propelled the larger dance theatre work. Indeed, the group succeeded in presenting itself as a professional level dance company with an acute understanding of their choreographer’s artistic aesthetic. This attribute speaks volumes to Becky Beaullieu Valls’s ability to not only effectively teach dance technique but to instill the sense of diligence and intelligence needed to create a contemporary dance artist. This ability is essential at the collegiate level, as we should not only be training dancers bodies but minds as well.

Becky Beaullieu Valls’s aesthetic was always clear but her point of view was really cemented when she herself performed with her dancers. Becky Beaullieu Valls was captivating on stage and the command she demonstrated over her body and performance was impressive. In seeing her perform I became even more aware of the ensemble she had created and how she had trained her company not only to be beautiful dancers but also to be performers that lived in the world of her choreographic aesthetic.

Dance is a collaborative art form in general because we are working with human beings and not paint, materials, or words but the collaborative nature of Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria was a multifaceted collaboration that had an effortless integration by the time I saw the work. This is certainly another important attribute for a dance artist, faculty member, and professor to possess. Having the tools to successfully navigate a myriad of views while maintaining one’s own voice is an art in and of itself and is often a skill needed at Universities.

When I was asked to write this peer review for Becky Beaullieu Valls based on one viewing of an evening length multi media choreographic work I knew I wanted to be as honest as I could be. I decided to wait and write the peer review so that I could truly respond to what ideas, images, movement, and art I retained after a month. I have seen more dance work than I am able to recount but what follows is the remains of my Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria experience.

On Saturday, March 3rd, I saw Becky Beaullieu Valls’s collaborative evening length dance theatre work Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria. The work had abstraction while maintaining a grounded foot in reality, creating a successful weaving of mediums and ideas. Memoirs of the Sisterhood– Chapter Three: Ave Maria was a textured journey of images, film, movement, and visual art that gave a glimpse in to women, maturation, family dysfunction, and the effect religion can have on those concepts.

As you entered the theatre a female sculptor was actively working on constructing some female form. Off to the side of the stage (audience left) Babette Beaullieu maintained her methodical sculpting. The visual image kept shifting and growing referencing iconic images of femininity, sisterhood, and the catholic influence on those ideas as the work progressed. The sculpted image consistently making a comment on the performance as an aside or subconscious thought of the performance itself.

The entire evening was supported by the religious sounds of Magnificats, Glorias, and Ave Marias setting the tone and research of Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria. Just as a religious service progresses, the work itself had that sense of structure, ritual, and reverence as the women on stage progressed in age and their relationship with each other deepened.

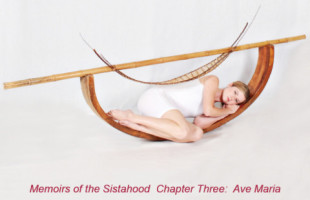

I grew up singing in an Episcopalian men and boys choir and the performance’s opening image reminded me of singing at the back of the church to set the tone and reflection for the service. As the performance of Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria began the audience sees a lovely wood sculpture with a womb like quality cradling a dancer. Simple and visually compelling this prologue guided the audience to the creative investigation without being overtly obvious.

During the “procession” of Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria we are presented with a film depicting these sisters as children interacting with family and as always the ever present church. As an audience I have now been presented multiple ways to invest with the story being told. Movement can often be too elusive for much of the general public but with the variety of frames Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria provided it helped to direct the audience so their relationship to the movement itself might become more profound.

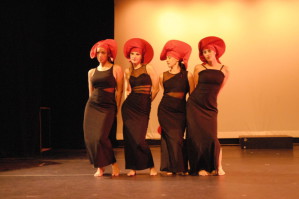

As the first Act progressed, much like growing up, there is fun, whimsy, angst, and I might even say a wee bit of highjinxs. Sweeping movement, high legs, partnering, and athletic technical dance moved us along as our heroines ascend in age. In a section that I can only assume is catholic high school they dance in headdresses to which crosses are affixed referencing habits. The first Act laid the groundwork and tilled the soil for the “communion” of the work. I left the theatre at intermission with something of substance to ponder but also entertained.

The second Act started with a bedroom type set, a classic white wedding dress, and a soprano thoughtfully singing an acapella rendition of Bach’s Ave Maria. For me, I was posed the question as to what women are left with and allowed to pursue after such an upbringing. Women are to be married and raise a family and why should one question or struggle against that very idea? So it was clear to me that we were headed for Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria’s “communion”.

The Mother (Becky Beaullieu Valls) appears with her societal and religious construction and constraint. Her stoic reserve and acceptance permeates the space and reinforces the questions about women, options, and their relationship to society as a whole. How did each one of these sisters react or follow in their matriarch’s footsteps? How did they support and react to each other during all of this and what are their relationships to these ideas now? My mind kept swirling to these questions and thoughts as mothers, daughters, wedding dresses, and rituals played out in a myriad of ways on stage.

There was exciting dancing sweeping through the space, bounding motion in and out of the floor, simplistic gesture, and compositional movement invention present in Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria. Movement that added to the emotional subtext of the work, created an active reprieve from the topic, and connected different creative mediums. The visual and audio components of the work created the frame in which the choreography could live and explore.

I found that what I refer to as the mother section to be the gestalt of Memoirs of the Sisterhood – Chapter Three: Ave Maria with it’s textured images and feminist questions. At one point each women lies flat on their stomach and puts their arm across another’s back. A diagonal of female familial representation is left on the floor. A moment that merges movement, theatre, and visual art, this image somehow encapsulates the entire work for me. The line of what is dance or theatre or art becomes blurred creating a question, a comment, a moment of reflective beauty and that seems to be the point of artistic endeavors in the first place.

I would have no hesitation about recommending Becky Beaullieu Valls as a teacher to any of my students or colleagues. There is no doubt in my mind that she has an in depth knowledge of dance technique, composition, and choreography and I am sure she is able to disseminate that information to her pupils. These things were abundantly clear after seeing her choreographic work.

Art and Culture Magazine

December 2011 + January 2012

Memoirs of a Sistahood - Chapter Three - Ave Maria

DiverseWorks

November 17 - 19, 2011

The Beaullieu sisters, Becky Beaullieu Valls and Babette Beaullieu, turn their

memory sourcing minds toward their Louisiana Catholic upbringing in the

1950s. The Virgin Mary was huge for their family, especially their mother.

Mixing dance, sculpture, video and text, the sister team weaved a loosely narrative

tale that sustains itself more from its bright spots than its overall cohesion.

“Memoirs of a Sistahood-ChapterThree-AveMaria” didn’t find its groove

until Act II, where the most potent dancing and images occurred. A mother

daughter duet, sparely danced Toni Valle and Valls, had the dancers tethered by

a shroud, reminiscent of the sheer veils obscuring statures of the Virgin Mary.

The two struggle, reconcile and struggle again, revealing the complexity of their

relationship, especially when you are one of many daughters.

A second, more agitated duet, danced by Valls and Joanie Trevino, contained the

most intriguing movement vocabulary of the evening, and a rare chance to see

Valls move. She’s an intelligent dancer with an authority to her shapes, holding

the space with a quiet reverence and depth rarely seen onHoustonstages.

Well into her 50s, Valls carries all that she knows into her movement, showing

a grounded quality, a studied grace and a modern dance nobility. She’s like

a great mother eagle when she spreads her wings.

Although her dancing became the corner stone of the piece for me, it still

couldn’t be the glue that held the entire work together. Slow transitions between

sections interrupted the flow, making it more episodic, as if each section was

made separately, then strung together. Perhaps memory is a fuzzy thing, and

the structure mirrored that. Yet, it felt more of a production problem. A redundant

video of Virgin Mary statues didn’t add much either.

During the course of the show, Beaullieu methodically builds a sculpture of

a woman’s form with wire, twigs, beads and other objects. By the end, the piece

becomes enshrined into a cavern of branches, as if the sisters have reinvented

their own Virgin Mary.

-NANCY WOZNY, Editor nancy@artsandculturetx.com

Choreography, Film, Sculpture Merge in ‘Memoirs of the Sistahood’

Mike Emery, UH Media Relations

Blood is thicker than water…especially when sibling artists work together on the same project.

UniversityofHoustondance professor Rebecca Valls is well aware of this fact. She and sculptor sister Babette Beaullieu collaborated on the “Memoirs of the Sistahood” series. These multidisciplinary performance pieces are focused on Valls and Beaullieu’s large family (six sisters) and Catholic upbringing inLouisiana.

The series latest installment “Memoirs of the Sistahood – Chapter Three: Ava Maria” runs Nov. 17 – 19 at DiverseWorks Art Space.

Valls took up dancing after seeing her first modern dance concert as an interior architecture student at the University of Louisiana (UL). She completed her interior architecture degree and quickly began a bachelor’s degree in dance at UL. She later earned a master of fine arts in dance fromSarahLawrenceCollegeinNew York.

After working with several dance companies inLouisiana, Valls found her way toHoustonin the early 1990s. Since then, she’s been an active force inHouston’s dance scene. At UH, Valls directs the UH Dance Ensemble and the Young Audience Touring Program, which introduces modern dance to local elementary schools.

Creative Pride caught up with Valls at UH to talk about the challenges of working with family and for a preview of this third chapter of “Memoirs."

Creative Pride: For those who have not seen previous “Memoirs” performances, what should they expect?

Rebecca Valls: “Memoirs” is a dance theater production that is multidisciplinary. My sister, Babette, is a sculptor, so she provides stage sets and sculptured costumes. We’re working with Deborah Schildt, a filmmaker from Anchorage, Alaska. She creates films for us and intercuts our own Super 8 home movies. It’s our three art forms coming together.

Me and Babette have chosen themes based on our family stories. Our work is biographical, but it’s non-linear. Rather than developing a story, we juxtapose imagery. We both work on a more sensory or visceral level, so we want the audience to respond in that way.

CP: So, there’s a lot happening on stage.

RV: Yes, especially in this production. It’s focused on a few things…my sister building a sculpture during the performance, the movement of the dancers and the film.

CP: What was the inspiration for “Memoirs?”

RV: I initiated it because my previous work as a choreographer included these 20-minute dances that were based on different content areas. After a while, it wasn’t very satisfying. To work on in-depth, multidisciplinary work was very challenging and something that I could sink my teeth into.

CP: Tell me a little about how the films will fit into the performance.

RV: Deborah produces two films for the show. One is based on our home movies. She creates the other one. For this show, she went to Louisiana and filmed statures of the Virgin Mary that were in people’s yards. That film is titled “Drive By Marys.”

The threads that connect this show are memories of my mother, the relationship of my sisters to her, her devotion to being a Catholic and the Blessed Virgin Mary.

CP: What’s it like working with family?

RV: It’s fun but also trying. Yesterday, we had a little battle, and when stress levels are high, we can both become agitated.

When you’re dealing with family, you’re more prone to not be as respectful as you would be with strangers. If I were working with someone who wasn’t my sister, my boundaries would be different. But, you get through it and the difficult moments pass. Overall, it’s great to collaborate on a project like this with my sister.

CP: This is obviously a very personal project for you and your sister. How do you think audiences will respond to this work?

RV: Everybody has a memory of their mother, so they may be touched by this show’s emotional content. There are videos that are very accessible and text with real people…my sisters…talking about their mother. There may be some abstract passages, but the mother-child concept is timeless.

Preview: Becky Valls Memoirs of the Sistahood - Chapter Three: Ave Maria

The Movement of Life

Choreographer Becky Valls

Finds Inspiration in

Autobiography

By Holly Beretto

Dance Source Houston, November 17, 2011

“We have a colorful Catholic family in Louisiana,” laughs Becky Valls, two weeks out from the opening of “Memoirs of the Sistahood: Chapter Three – Ave Maria,” (http://memoirsofthesistahood.com) the latest installment of her multimedia collaboration with her sculptor sister. “And I used the content from our family as a springboard.”

“Memoirs of the Sistahood” began in 2007 with “Chapter One,” which examined female archetypes and continued two years later with “Chapter Two – House,” an exploration of home and the possessions we carry with us. The projects bring to bear the talents of Valls, a Houston choreographer and performer known for her modern dance work; her sister Babette Beaullieau Wattigny, a New Orleans-based sculptor; and Alaska-based filmmaker Deborah Schildt, whose work includes everything from documentaries to commercials. All of the chapters incorporate dance, art and film, telling the stories of the six Beaullieu sisters and their coming of age in 1950s Louisiana, as well as echoing on a larger scale what it means to be human.

Valls, her sisters and “one lone brother” were raised in New Iberia, Louisiana. Their father was a doctor, but Valls says there was a great deal of creativity in their family, so there was no real surprise that she gravitated toward dance and the artistry and invention it entails. While Valls and Babette are the only working artists in the group, Valls says that there is tremendous familial support for what they do. Valls is both pleased and proud as she points out that her extended family has attended the opening of all the project’s chapters.

As fans of “Memoirs of the Sistahood” will recall, each piece in the ongoing story tells another tale of family life. And, even as Valls uses her own family experiences as a jumping off point, she believes that the concepts of family and belonging resonate across cultural and ethnic lines.

“It’s a sensory experience,” she says of “Chapter Three – Ave Maria,” which opens at Diverseworks on Nov. 17. “I hope the audience will think of their own relationship to their own mothers.”

In it, Valls also explores the sacred devotion Catholics have to the Virgin Mary, and what the concept of motherhood means. She approaches her examination of these topics with both humor and reverence. As the dancers tell their story, Valls’ sister Babette is on stage, creating a sculpture, and film clips from “Chapter Two – House” will be shown.

“There’s such imagery,” Valls says of the staging. “Babette has these rocking boats that help define the nurturing aspect of motherhood, and that offers a wider impact for the audience than just the telling of our family story.”

In addition to the on-stage dancing, film and art installation, “Chapter Three - Ave Maria” includes on-stage singing by performer Natasha Manley, and music from singer Hildegard von Bingen and Foufollet, a Cajun folk band whose contemporary sound impressed Valls and her sister. She’s also using work by Vivaldi and Zoe Keating.

“So many modern dancers are attracted to Zoe Keating’s overlays and soul sound,” Valls muses. “And I love Hildegard; her airy voice just brings you to a spiritual place.”

Valls appreciates both the inspiration provided by her family as well as the opportunities dancing has afforded her. She’s been performing and choreographing for more than 30 years, and counts herself lucky in being able to still do so. Collaborating with her sister is an experience she treasures, although she admits that while working on each aspect of Memoirs of the Sistahood, there were – and are – times when it seems that she and Babette are only talking about work.

“We’ll be at a family gathering and instead of kicking back, being sisters and talking about life, we’ll be there talking about how the project is taking shape. It’s a strain sometimes, but we still value that we can do this.”

Performances of Memoirs of the Sistahood: Chapter Three – Ave Maria run Nov. 17 – 19 at Diverseworks Houston. For tickets, visit www.diverseworks.org

Following the opening night performance, audience members can meet the dancers, Babette and Valls at a complementary reception.

And encore presentation of Memoirs of the Sistahood: Chapter Three – Ave Maria will be held at the New OrleansContemporaryArtCenter on March 2, 2012.

Connections and Crossroads:

Dancing After 40

By Toni Leago Valle

November 3, 2011

When I performed with Jane Weiner and the Pink Aware Dancers for six seasons, there was a video about Jane and her sister to show the history of how they started Pink Ribbons. It began with, “Jane is a dancer.” I miss the days of Joe backstage, without fail, replacing the last word: “Jane is an archeologist. Jane is a hot-dog vendor. Jane is an underwater aerialist. Jane is a quadriplegic performing artist.” However hilarious this always was, it is the perfect metaphor – that dancers are so much more than the person on the stage.

Since turning 40 a few years back, I’ve been watching dancers, talking to dancers too, but mostly watching them. The dancers I’ve been attracted to onstage are the ones who also attract me offstage. The ones whose lives are much more interesting when the curtain closes. People who not only take the diverse pathway, but also live it at full throttle, glide the obstacles, and affect the world they live in with such powerful grace and dignity, that others cluster to them, not knowing what they seek but knowing they have found it.

Putting existentialism aside, I am at a crossroads in my career as a dancer and choreographer. After leaving company life to take care my son Dante, last year I decided to rejoin Karen Stokes Dance as a full season company member. This was my first time in six years that I would be dancing 5 days a week, between 3-5 hours a day. I was excited to be a part of the concert The Secondary Colors, but I wondered if, at 42, my body could handle it. Almost before the thought took hold, I rejected that idea and earnestly went into training.

In May, Becky Valls asked me to be in the third installment of the Memoirs series. At 42, could I rehearse and train two shows back to back? Could I actually look like a sister next to performers in their prime: Kristi Farr, Joani Trevino, Mallory Horn, Nicole McNeil and Natasha Manley? The answer is yes. At 42, I have found that I am not as physically strong as I once was, that my mind is slower and I cannot always keep up in ballet class, and I have to rehearse outside of rehearsals in order to get the material in my body, but it can be done.

And while I’ve been eating, sleeping, training, and living dance since May, something else has been percolating in the wings. That I not only live to dance; I live for the connections I make with other dancers. Over the past two years, I have served as confidante to four pregnancies before they were public, (like I’m the best person to keep a secret - haha), the private life of a friend where hope and life can be different and better, and the backstage person to lean on. Knowing the person behind the develope, I feel full, needed, connected, and important that others wish to connect with me.

By nature, the dance world is full of families and also by nature, as a dancer moves from one company to the next, family ties are broken to make room for new ones. I look back and miss my families: Suchu Dance, Hope Center, Psophonia Dance Company, Dancepatheatre, Travesty Dance Group. Some friendships have endured past the working relationship, but others I am lucky to see at performance.

SO, as I go into tech week next week for Becky Valls’ Memoirs of the Sistahood Chapter Three: Ave Maria, for me, the Memoirs family is a symbol of both the “Beaullieu sistas” onstage and my dance family offstage. I’ve worked and played with all these women, including Becky, for years, and it shows in the ease of performing together. I have a particularly stirring duet with Becky that touches my own familial roots and I’m honored to perform it.

Then I will once again be faced with the old dilemma: how to maintain my dance family once the show is over. So, heads up - I am beginning a journey over the next year to connect with dancers and get their stories. I’m just plain bored with my own stories. Because, as you will see in Memoirs, it’s not the story that’s exciting; it’s the telling.

Memoirs of the Sistahood Chapter Three: Ave Maria opens November 17-19, 2011 at 8pm, at Diverseworks. For more information, visit www.memoirsofthesistahood.com

Memoirs of the Sistahood Chapter Two: House

Members of a large Catholic family who experienced childhood in southern Louisiana during the 1950s,

sisters Becky Beaullieu Valls and Babette Beaullieu build upon a rich soil of memory for their dance theatre collaborations, Memoirs of the Sistahood. Nearly two years after the

debut of Chapter One, the duo has delivered their second installment, Chapter Two: House. A video recap opens the show. Even to the uninitiated, however, the

visual prologue is nonessential. This production is sufficiently distinct. Like a house, it is intelligently designed with pattern, substance, and mortar structured around a supportive

framework.

Of course, every house needs a hostess. In a vintage cinch-waist dress, narrator Kathy Hallmark delivers an introduction with the saccharine, matter-of-fact tone of a 1950's television housewife.

"All houses are dwellings," she quotes Paul Oliver's reference book on vernacular homes throughout the world, "but not all dwellings are houses. To dwell is to make one's abode: to live in, or at or

on, or about a place." Like Oliver’s book, Chapter Two: House, examines different types and ways to dwell.

Valls glides between choreographic modes as easily as one might move from room to room. She begins with a minimalist, pure movement

approach, then displays skillful confidence as the work shifts to burlesque. In Act I, which examines dwellings as structure, Valls shows restraint, choosing not to hide or overdress the circles,

lines, and spatial devices that form the skeleton of her choreography. Later, Busby Berkley inspired formations give way to a lively mambo, danced by sepia-toned housewives armed with cornflake boxes

and kitchen gadgetry.

Veteran performers, including Valls herself, anchor the company. Dancers, Toni Leago Valle, Jenny Dodson (formerly Magill), and Joani Trevino are consistent in their actualization of Valls' smooth,

expansive movement style, and they transition easily to comedic and presentational delivery.

Clearly, the collaborators are all on the same page with House. Deborah Schlidt’s dreamy film collage weaves in and out of the action as naturally

as any performer making an entrance. Images of various types of dwellings, from hovels to tract houses, segue to demolished and water-logged homes. Reclaimed by nature with the brute force of

Hurricane Katrina, these homes (or ones like them) may have given up parts of themselves for repurposing in Babette Beaullieu’s found object sculpture and set pieces. Dancers first appear in costumes

the color of clay and mud. Attentively designed by Cherie Acosta, these basics are detailed with netting and natural fabrics that echo the weathered patina of the doors, windows, and boxes Beaullieu

has fashioned to represent the family homestead. Among these pieces, a playful dinner scene and a bed of sleeping children are given a hazy luminescence by lighting designer Kris Phelps that recalls

precious home movie footage of the Beaullieu family.

It all works together, even as these collaborators rather craftily bring their 1950s backdrop to the forefront. I Love Lucy clips play dreamily as

the childhood game of playing house transitions effortlessly to a satiric portrayal of real life domesticity. Text from Housekeeping

Monthly's "The Good Wife's Guide" illustrates the expectations and constraints placed on women saddled with running a home. Fifties era musical selections such as the Dean Martin

classic, Sway, fuel the wry comedy which culminates in a kitschy "mobile home" show. The dancers flaunt their best runway sashay in a segment that

in lesser hands could have capsized the production.

The milieu of 1950's iconography remains upright however because Valls and Beaullieu, with their collaborators, thoughtfully maintain a through line. It is no small feat to coalesce this array of

concepts. Chapter Two: House reaches coherence because the team has built a solid framework and follows-through with strong images and clear

ideas. The enchanting and harmonious collaboration brought the audience to their feet on opening night.

Nichelle http://nichelledances.wordpress.com

Memoirs of a Sistahood - Chapter One

Diverseworks

December 7, 2007

By: Nancy Wozny

I thought childhood was pretty much about learning to tie my shoes, getting along with a slew of people who all have the same nose, and generally speaking, growing up. After seeing Memoirs of the Sistahood – Chapter One, a new work by sisters and collaborators Becky Beaullieu Valls and Babette Beaullieu Wattigny, I see childhood in a whole new light—it's about gathering material, for what else, a smashing show. All that time the Beaullieu sisters, Beth, Becky, Babatte, Bonnie, Bitsy, and Barbara, where trying to make it to church on time, they were really rehearsing. And what a rich soup of material sisters Valls and Wattigny have to play with, growing up in a Catholic family in Louisiana during the 1950s.

The Beaullieu sisters create a dreamscape with Wattigny's sculptural pieces that transform into portals for Valls' dances. Using decorative back porch doors, intricate narrow closets that resemble medieval alter pieces, and rustic window frames, Wattigny colors and covers the stage with entrances, exits, and hiding places. They serve to let the performers weave in and through their own whimsical logical time line and completely free us from any linear narrative. Glorious stage pictures elegantly frame Valls' dances.

Valls crafts her choreography from a fluid post modern dance style, while also playing off recognizable gesture and everyday actions. As each sister enters from one of Wattigny's colorful back porch doors in a slow motion dirge, they carry a sculpture crafted from nature on their backs, as if to resurrect something from each of their pasts into the present. One carries a collection of sticks, another a vessel, symbolic of traveling through time, each with a distinct gift. One ensemble section completely conjured the tight living quarters six sisters must have survived. Valls herself danced a sweet duet with Mechelle Fleming. One wonders if Valls here is a time traveler and is dancing with herself.

All collaborators contribute to Memoirs' sense of wholeness. The sound score combines eerie tunes from Dead Can Dance and the like with Misha Penton's ethereal instrumental pieces. Kris Phelps' lightening emphasizes private spaces and a suitably dreamy atmosphere. A video montage by Deborah Schildt also hopscotches through time, landing on memorable moments, birthdays, holidays, vacations, giving us a glimpse of family record without a litany of actual events. Costumes by Valls and Wattigny draw from Louisiana folklore, 1950s fashions, and southern debutante glamour. On a post-show close inspection, one costume reveals a trim of doll parts, and other junk drawer delights. Both costumes and sets hold their own as an installation piece as well as a performance. In fact the piece concludes by the performers bringing all the visual elements together for one last look, a final tableau.

The capable performers included Kara Ary, Mechelle Flemming, Jennifer Magill, Stephanie Rodriguez, Joani Trevino, Toni Leago Valle, and Corian Ellisor (as the solo male child). Valls and Wattigny made smartly positioned cameo appearances as well.

A few bumps down memory road included: an occasionally overly cluttered stage, abrupt and long blackouts, and some sheer practical concerns about moving such intricate and complex objects on and off stage.

There are many lovely elements to this work, but chief among them is the pair's commitment to telling a new story rather than falling into the dreaded page-from-our-journal- autobiographical-syndrome. There's little attempt to use personal history as just that, the truth. Memoirs of a Sisterhood – Chapter One derives much of its drive from mining the power of memory alone, most specifically the embellishment of imperfect recollection. Memory is a dance, an art in and of itself. Memory can only be a creative act. When we remember we re-create; Memoirs enlists this process exactly.

A scene with all seven children waving from a speeding boat proved my point about the meaning of childhood. They are waving at us from the past, as if in that actual moment, they all knew that it was a keeper.

I doubt I was the only audience member who wanted to wave back in thanks for the Beaullieu family coming into my life.

The Times-Picayune Thursday, March 26, 2009

'Sistahood' exhibit returns to its roots

Beaullieu sisters focus on '50s in La.

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

By: Linda Dautreuil

There is a buzz about a performance launched late last year in Houston that's making its way to New Orleans this spring. "Memoirs of the Sistahood - Chapter One" is coming home to Louisiana.

The performance is the first in a series of collaborative works between sisters Babette Beaullieu, a sculptor and teacher in the St. Tammany Talented Arts Program in Mandeville; Becky Beaullieu Valls, a performer/choreographer living in Houston; and independent filmmaker Deborah Schildt of Alaska. "Chapter One" focuses on the female archetypes of 1950s Louisiana and the six Beaullieu sisters: Beth, Becky, Babette, Bonnie, Bitsy and Barbara.

Based on the experiences of growing up in a large Catholic family, the series fuses individual artwork created by the artist-sisters with childhood "sense memories," original music and film. Central to the interactive stage setting is Babette Beaullieu's life-size altar boxes of wood and organic materials representing the complex personality patterns of family.

The sculptures appear onstage to house the dance performers and are exhibited after the performance for audience viewing.

Recognized most recently for her exhibition, "Hidden Spaces: Mixed Media Sculpture" at the Shaw Center for the Arts in Baton Rouge, Babette Beaullieu is known for her use of found materials to create large-scale three-dimensional sculptures and wall reliefs.

She built the six altar boxes for Chapter One with recycled materials found on the streets of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

Windows, doors, wood and architectural details came from torn down buildings and trash piles. Beaullieu notes, "I built a box, not really thinking at first which sister I was trying to represent. Halfway through the construction, I began to sense a specific energy, how it felt to be with that sister. I could hear our conversations. I think of these altar boxes as spiritual totems that are also universal archetypes."

When Chapter One premiered in December 2007 at Diverse Works Art Space in Houston, critics may have expected a sentimental memory play, but the visual and kinetic storytelling drew rave reviews as new material rather than simply reminiscences of the past.

The Contemporary Arts Center will present "Memoirs of the Sistahood, Chapter One," with interactive sculptures by Mandeville visual artist and teacher Babette Beaullieu April 4 at 8 p.m., onstage at 900 Camp St., New Orleans.

Tickets for the general public are $20, $18 for students, and $15 for seniors. For more information, visit www.cacno.org.

Published on NOLA.com Wednesday, March 25, 2009 1:22 p.m.

Published in The Times-Picayune Thursday, March 26, 2009

Memoirs of the Sistahood - Chapter One

DiverseWorks

Houston, Texas

December 7, 2007

By: John DeMers

Copyright ArtsHouston Magazine, January 2008

Works of highly private inspiration have a long and distinguished history of being poor public entertainment. That fact alone makes this dance-filled “memory play” by choreographer Becky Valls and her sculptor sister Babette Beaullieu Wattigny and achievement more than a little notable. As presented at DiverseWorks, Memoirs, was “private” in the way that a short novel might be, or perhaps a small experimental film free of major stars. But it seemed a departure from most dance evenings – even from admittedly boundary-free “modern dance”. Memoirs was cinematic more than anything else, an act of visual storytelling that used dance along with projected film, exquisite music and intriguing sculpture. In short, it worked.

We’re not sure exactly why “sisterhood” was expressed in the title as “Sistahood,” since that seemed “ghetto” in a way that neither the creators nor their creation were or wanted to be. The story involved the interwoven lives of six French Catholic sisters coming of age during the 1950s in French Catholic south Louisiana. Anytime there was a specific reference in Memoirs, that was the place and the time. Yet nearly all the individual, almost unrelated dance segments were either too ambiguous to be about anything, or too universal to be limited to any single thing. The core experience was growing up, specifically as a girl with lots of sisters – through life with lots of siblings was common enough amongLouisiana’s French Catholics. The evening floated by as a series of half-remembered, possibly half-dreamed vignettes, news clippings from a youth presumably remembered from the distance of age. That last conviction seemed to grow from the way Valls looked at even the most light-hearted of family times with longing, as though reaching out to them across the decades without ever truly reaching them. Nostalgia? Perhaps. But not the cheap, store-bought kind. This was passion for an essential past, coming from a very deep, sometimes dark and ultimately loving place.

The visible center of Memoirs was the graceful, loping, curling and circling choreography of Valls, who also serves as director of the dance program at Rice. There were clear debts here to that other chronicler of ever-symbolized young womanhood, Agnes DeMille in such pieces as her ballet for the musical Oklahoma. The dancers always managed to entertain while emotionally affecting us, and never more than in those segments featuring Valls herself. Her facial expressions and movements were the “voice” of the narrator, even though she and her sisters also provided spoken words to set up many of the scenes.

All pieces were delivered with enthusiasm, capable of acting and absolute belief by Kara Ary, Mechelle Flemming, Jenny Magill, Stephanie Rodriguez, Joani Trevino, and Toni Leago Valle, with an entertaining assist from Corian Ellisor, the lone male allowed into this sleepover. Sets and props were mostly pieces created from old wooden doors, windows and other found objects by Wattigny. And the evening’s most touching backdrop was an incredibly edited montage of family home movies, tossed up on a screen in all the scratchy wonderment of people, places, and things never to be seen again. Except that, thanks to this particular and talented sisterhood, they can be. And they were.

News

Becky received tenure at University of Houston and is now an Associate Professor.